In Chapter 3 of my forthcoming book, Sovereign Joy: Afro-Mexican Kings and Queens, 1539-1640 (Cambridge University Press, 2022), I study, among other performances of festive Afro-Mexican kings and queens, a private party a group of Afro-Mexicans held on Christmas Eve, 1608, in Mexico City. In the anti-Black world we have been living in since time immemorial, these Afro-Mexicans were denounced for their “boldness” (avilantez) to a local judge. And in the paradoxical way in which we learn about the Black past, especially the colonial past, and although the party is also mentioned by two other contemporary sources (the viceroy and a cleric), the judge’s report is the longest account of the event (six double-sided folios). In his report, which called for the wholesale slaughter of Afro-Mexicans (“que [hombres de confianza] los puedan matar [a los cimarrones] libremente” [that (trusted men) may freely kill (runaway, formerly enslaved Afro-Mexicans)]), the judge tells us that, after crowning a royal court, the gathered had a “famosa cena” (great banquet) and danced. Although I note in Sovereign Joy that this example shows that feasting was central to Afro-Mexicans’ colonial lives, I had never thought too much about the food that may have been consumed at the banquet.

Then on February 22, I received an email from Mr. Zach Steen, chef de cuisine at Mr. Rick Bayless’ Frontera Grill in Chicago. Mr. Jason Maurice Yonover, an acquaintance of Chef Steen’s and Ms. Javauneeka Jacobs’, the youngest and first African American sous chef at Frontera, had seen my tweet of the title page of the proofs of Sovereign Joy and mentioned the book to Chefs Steen and Jacobs. Chef Steen was writing to invite me to a tasting of Frontera’s Afro-Mexican special menu, which he, Chef Jacobs, Mr. Richard James, also a chef de cuisine at Frontera, Mr. Jonathan Cisneros, a line cook in the restaurant, and Ms. Jennifer Meléndrez, Frontera’s pastry chef, had engineered for Black Heritage Month.

On February 26, my wife, Dr. Anna J. Valerio, a friend, and I sat down for a mouth-watering culinary and sensorial tour de force. We were served five appetizers, four courses, and two desserts inspired by the Afro-Mexican cuisine of the states of Guerrero and Veracruz, home to most Afro-Mexicans. One, “Chicken, Black Bean Sauce, Plantain,” whose black bean and red chile sauce Mr. Cisneros had first tasted from his grandmother and helped the team bring to grandmotherly perfection, as Chef James shared with us, also features golden plantain and chicken chicharron, staples of Afro-diasporic cuisines. As the team shared with us, they started with to slim cookbooks in Chef Bayless’ voluminous library. (Both the team and Chef Bayless – who dropped in to greet us – complained about the scarcity of sources, something those of us who do research on Afro-Mexico know all too well—I only found five documents for my book.

The menu, which runs through March, also includes two vegetarian options: a roasted cauliflower and a sweet potato-based dish on a delicious jam.

Both Chefs Steen and James shared that the dishes they found in the cookbooks or heard of from Mr. Cisneros had a lot in common with insular Caribbean and African American cuisines. I too had this sensation, particularly with the first appetizer, “Mariscos Enamorados” (Seafood in Love), a seafood salad from Guerrero eaten on crackers. It reminded me of seafood salads I had as a child in the US Virgin Islands.

There were also yuca con mojo (steamed cassava roots in a garlic sauce) and moros y cristianos (rice and beans), two staples of the Caribbean diet. These shared foodways, as I share with students when teach a unit on the African influence in Latin American cuisine, underscore shared roots and connected networks of involuntary (and sometimes voluntary) movement of Black people and culture throughout the region.

In 1608, the Afro-Mexican festive king was crowned by the viceroy’s pastry chef, just as Chef Meléndrez crowned our sensorial feast with “Empanada Tropical” (a delicious, sweet, cinnamon sugar-coated empanada filled with arroz con leche) and “Plantain Layer Cake” (a rich cake with plantain “Foster” layers, coated with fudgy chocolate).

I had never dreamt that something like this could come from my book. I am eternally grateful to Mr. Yonover, Chef Bayless, Frontera’s team, and the ancestors, who made this possible. I cannot imagine a better way to culminate the seven years of research that went into it.

-By Miguel A. Valerio, Assistant Professor of Spanish

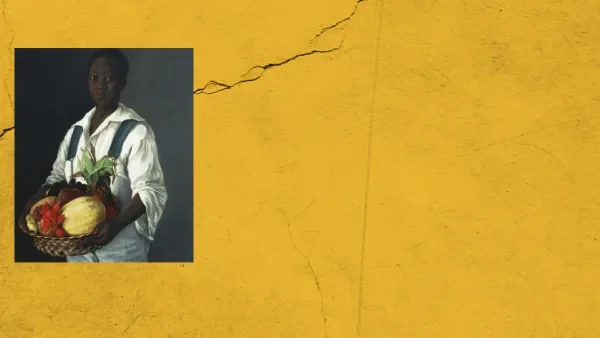

Header Image: El Costeño by Agustín Arrieta, a painting of an afromexican boy from Veracruz (c. 1843)