In a new book, Miguel Valerio uncovers the history of Afro-Mexican festival performances in colonial Mexico.

Following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, scholar Imani Perry wrote in the Atlantic about the importance of acknowledging joy alongside suffering. “Blackness is an immense and defiant joy,” she wrote. Miguel Valerio, assistant professor of Spanish in Arts & Sciences, found inspiration in this idea of defiant joy. Valerio was finishing a book about Afro-Mexican festival performances in which Black men and women created spaces for sovereignty despite being enslaved. Defiant joy perfectly captured the importance of his research uncovering this history.

“I was reminded of the centrality of joy to the way that people throughout history have sustained the struggle for their rights,” Valerio said. “There is an alternative sovereignty to their joy, and there is also a joy to sovereignty, to the way that they claim their right to be free.”

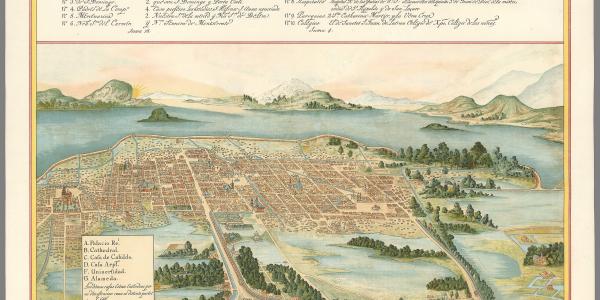

In Sovereign Joy: Afro-Mexican Kings and Queens, 1539-1640 (Cambridge University Press), Valerio recovers the history of festival performances by Black people in Mexico City. In Europe, festivals in which ordinary people are crowned king and queen for the day have a long history. European colonizers brought the practice with them to the Americas, and its legacy continues to this day in events like New Orleans’ Carnival. In colonial Mexico, African and Afro-creole people combined the European tradition of the carnivalesque with African practices. Mingling baroque dances with African martial dances, Black performers created a space in which they could mourn their loss of self-rule while also creating a kind of performative celebration of sovereignty that challenged their enslavement.

Valerio argues that these performances showcase the formation of an Afro-Mexican culture, depicting a unique Afro-creole way of life localized in Mexico City. In one dance Valerio describes, women perform an allegory involving an eagle and a rose. The eagle traditionally represented Mexico in local symbolism, and the rose represents the Virgin of Guadalupe, who first appeared to the faithful among roses. On another level, the eagle represents the Spanish king and the rose represent the women dancing, who are enslaved in his empire. By using all of these elements, the women stake claim to a Mexican identity.

Such performances occurred during elaborate festivals held for community events, such as the inauguration of a new church. Colonial authorities purposefully included a variety of performances in order to demonstrate the wide reach of the empire, and these spaces would afford Black communities the freedom to bring their own culture to the displays. Indigenous and Black confraternities — lay Catholic brotherhoods — would organize festival floats in these processions.

Valerio recently co-edited a collection of essays about these brotherhoods, which connected Indigenous and Black communities in Latin America. The brotherhoods provided a space for cultural practices that resist racial hierarchies through religious practices. In this era of Latin American history, the Catholic Church was often more sympathetic than governmental authorities to the rights of Black and Indigenous people, making religious festivals a more open environment for these brotherhoods to explore their cultural identity as Afro-Mexican people.

Many Spaniards, however, found these performances threatening and subversive.

“At the time, slavery is being racialized as Blackness, and so sovereignty is seen as exclusive of Blackness,” Valerio said. “The expression of that sovereignty, that joy, in these festivals was seen by many as antithetical to the idea of Blackness.”

Though enslaved Black people participated in festivals throughout the Americas, Mexico was the only place where they were killed for their festival practices. At a Christmas party in 1608, an Afro-Mexican brotherhood crowned a royal court. The participants were arrested but later acquitted. In 1611, an enslaved woman was beaten to death by her enslaver. Though the murder of enslaved people was outlawed in the Spanish empire at that time, her killer faced no consequences. The brotherhoods of Afro-Mexican men organized mass protests in which Black kings and queens marched in protest of the murder and the government’s lack of response. Later, 37 of the protesters would be hanged and quartered.

In recovering this history, Valerio had to see past the perspectives of colonial accounts. The Afro-Mexican people who participated in these performances did not leave behind descriptions of their practices. Instead, Valerio relied on descriptions of festivals published at the time and accusatory documents written by colonial authorities who were unsettled by the displays of sovereignty from people they had deemed less than human.

“I hope I have done justice to my subjects by bringing out how they dealt with the world,” Valerio reflected. “They created moments of joy and community, despite the violent political implications of what they were doing.”